AN ANALYSIS OF USING GAMEPLAY MECHANICS TO IMPROVE TRADE SITUATIONS

by

Igor

Research supervisor

浩司 | Koji

- - Redacted “Names” and “Contact” info to avoid automated data scraping

- - Cartography chart updated (more detailed influences between Actors and Activities)

- - Abstract rewritten ; Notion page publication

- - Paper completed

Abstract

This study investigates the game mechanics used to make trading with an NPC a part of the gameplay experience, as a side activity, in order to open paths to more non-combat gameplay through the growth of in-game shop interaction. A broad selection of games from different genre were selected, to analyse what mechanics and activities they use during trade situations. This analysis resulted in the cartography of 4 major trade’s related activities (haggling, relationship, economy and inventory management), the analysis of their interplays with each other, the description of 11 mechanics. And, in a second part, the evaluation of 3 of these mechanics (in the context of their game) through the criteria of form, substance, learning curve and variety. The findings suggest that, as is, these mechanics lack depth to be a reliable side gameplay that players will often do and enjoy.

INTRODUCTION

BACKGROUND

Interacting with a non-player character (NPC) to trade resources is present in countless games. However, trade is rarely considered as a player activity that can be used as side gameplay, despite being present in many game-loops. Typically, it is reduced to a user interface without any gameplay interaction.

This paper aims to analyse which mechanics are used in games that choose to add gameplay to their trade, to draw an overview of the existing landscape. Then highlight the potentials and flaws of these mechanics.

This research is intended for game developers looking to enhance their whole game or universe by using trade as a gameplay tool, to focus their production effort on an existing player activity to add side gameplay into their game, to explore the development of new non-combat or trade related mechanics, or those who are curious of the current state of gameplay around trade.

OUTLINE

INTRODUCTION

- Process: How the games and mechanics were selected for the research

- Limitations: What is excluded from the research

- Definitions: Breakdown of important notions

- CARTOGRAPHY OF TRADE MECHANICS

- Defining the mechanic of trade: How transactions work

- Affecting trade: Which parameters affect trade

- 3 satellites activities: The recurrent activities around trade

- Game actors: Important figures structuring a game

- Mechanics of haggling

- Mechanics of relationship

- Mechanics of economy

- Mechanics of inventory management

- ASSESSMENT OF TRADE MECHANICS

- Lenses for game mechanics: Models to examine a game mechanic

- Case studies: Practical uses of the lenses

ABOUT TRADE AS THE CORE-GAMEPLAY

REFERENCES

1. PROCESS

This research aims to do a global analysis of mechanics related to trade.

I selected curated games and studied their mechanics around trade activity to conduct the analysis. Then, I extracted existing mechanics and grouped them by similarities and impacts.

The games selected were coming from 2 lists. One with recently released and popular games, filled by monitoring the popularity of newly released games over the last years. The other list focuses on games known for making trade differently. These games were found by searching previous works on the subject, looking in databases, asking communities and monitoring games.

Since the analysis aims to be an overview, individual mechanics from various games sharing determining similarities have been aggregated under single models. Thus, particularities specific to an individual game may be simplified or omitted from the big picture.

2. LIMITATIONS OF THIS PAPER

- Single-player, not multiplayer: I have limited my scouting of mechanics to single-player environments only. Since multiplayer environments would need a heavier background on social behaviour I don’t have.

- In-game transaction: Since laws regarding the use of real currency in games and gambling vary between countries, I decided only to treat trades interacting solely within a game. I selected games where trade resources: are non-monetised; have no real-world value; the transaction occurs within the game’s ecosystem and serves the gameplay; and the outcome of a trade is non-transferable outside the game.

3. DEFINITIONS

DEFINITION OF GAME MECHANICS

To define the inner functioning of a trade mechanic, we first need to determine what composes a mechanic in the context of this paper.

GAME MECHANICS are interactive black boxes, receiving an input (from the player and/or the game) and returning an output made visible through feedback [1].

e.g. A dash ability takes inputs from the player controller(= player input) and runs the given code and parameters to change the position of the player’s character(= output).

e.g. Relationship(= game input) with an NPC in an role-playing game (RPG) can modify the level of trust and impact dialogue options, vendor prices or else(= output) with this NPC.

DEFINITION OF TRADE

TRADE is the activity of buying and selling, or exchanging, goods and/or services between people or countries [2].

In games, the principle is the same, where “goods” can be extended to “resources” to cover situations like buying experience points (XP) for a character or health points (HP) from an altar, which make intangible and fantasy goods concrete in the context of games.

“People or countries” points to the whole spectrum of the player character (PC) and non-player character (NPC) which are allowed, by the game, to interact to exchange resources and/or services. Trade between 2 NPCs counts in the definition. For this paper, I contract this whole category as “characters”.

This gives us the following:

TRADE (in a video-game) is the activity of buying and selling, or exchanging, resources and/or services between characters.

As a reminder, only trades between the player and NPCs are covered in this paper.

I. CARTOGRAPHY OF TRADE MECHANICS

Figure I. is the result of my analysis of the game mechanics used during trade situations. The rest of this chapter is dedicated to explaining the different parts of the figure.

Figure I: Cartography of trade mechanics

1. DEFINING THE MECHANIC OF TRADE

Before looking at the bigger picture, we need to define what is trade’s fundamental mechanic.

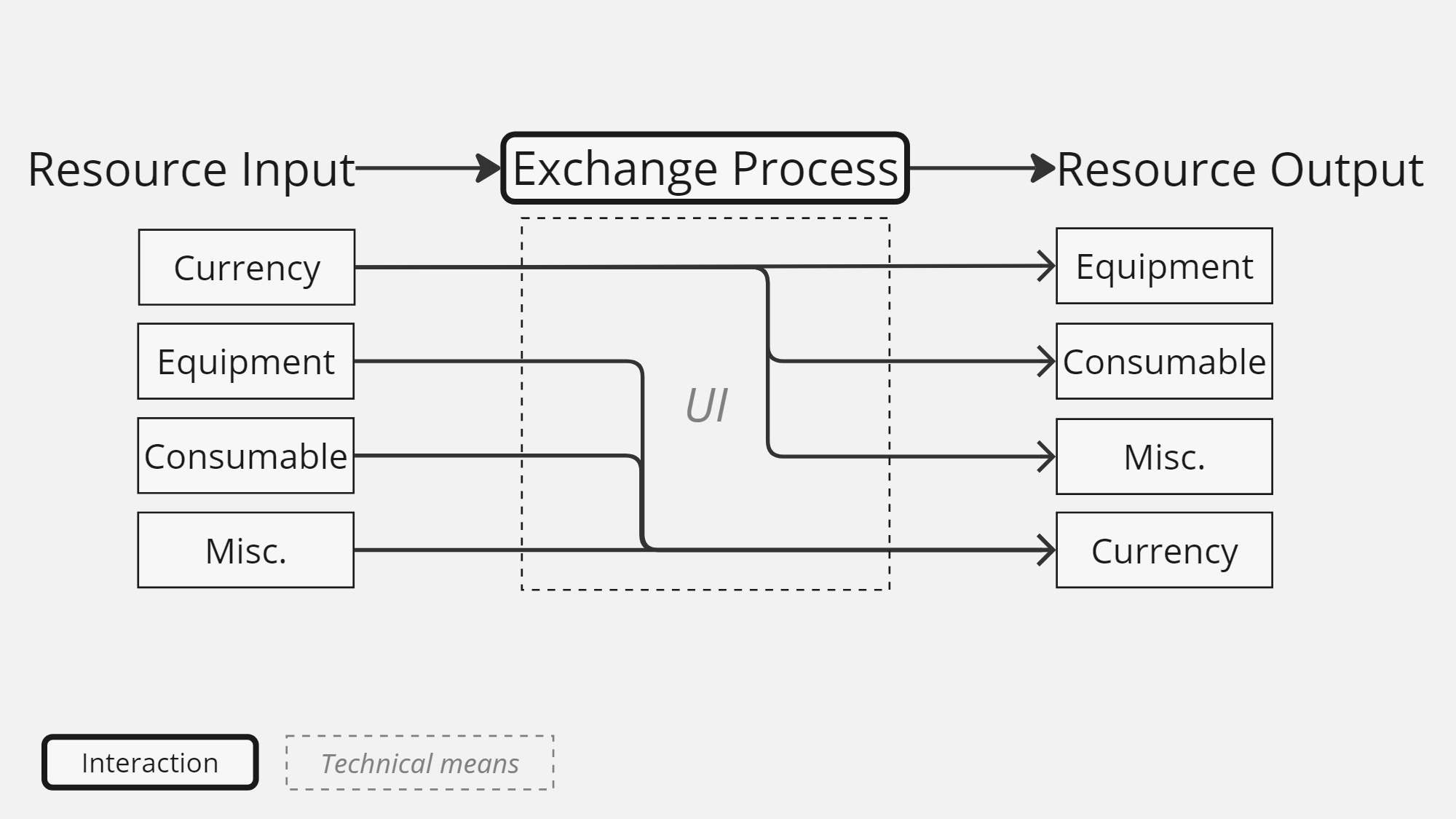

The fundamental of trade is its capacity to transform a resource into another one. A typical trade, in most games, between the player and a shop would look like Figure 1.

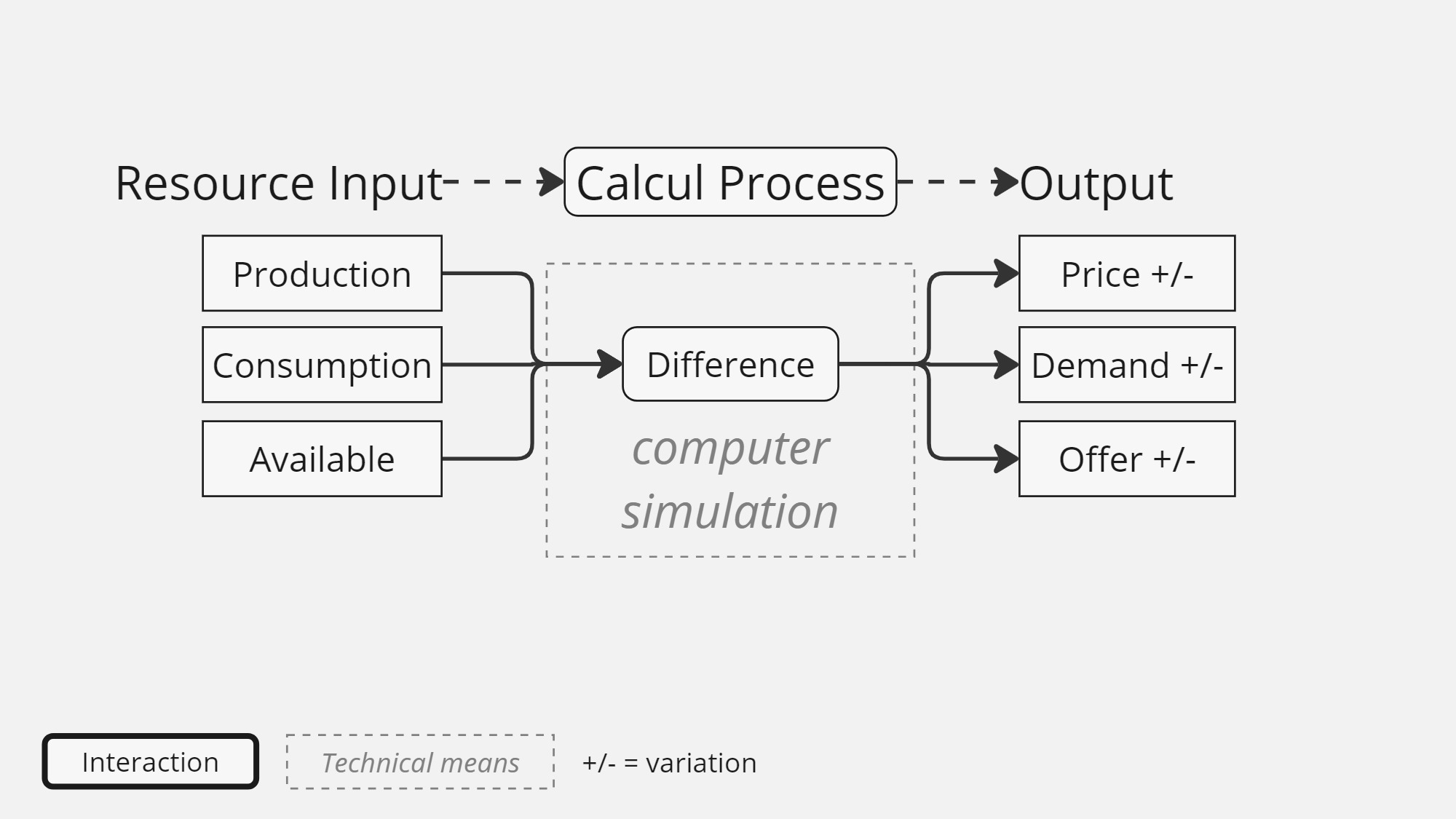

Figure 1: Visualising the transaction mechanic

- Input / Process / Output: Refers to the related elements in the game mechanics’ definition: Input / Black box / Output.

- Interaction: An element where the player must interact to trigger/resolve the activity.

e.g. Here, the player must interact to choose what resources to transform and trigger the transaction.

- Technical means: The computing foundation used to run the mechanic.

e.g. Here, a shop interface supports the exchange.

This mechanic is the core of a trade transaction and cannot be dissociated.

2. AFFECTING TRADE

First, it is important to know what parameters can affect a transaction. Understanding the different roles of gameplay activities around trade will also be useful.

There are 4 parameters which have a meaningful impact on trade:

- Appearance: The form of the activity delivered to players. It impacts primarily the mood and the practicality of trade.

e.g. “Baldur’s Gate 3’’(2023) shop interface is made for detailed navigation between plenty of objects, while the “Lethal Company”(2023) console command’s shop adds to the overall vibe of scrappiness of the game. The shop in “The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening”(2019), where Link needs to take the goods to the cashier, adds a sense of presence and physicality like in a diorama, a miniature garden or a doll house.

- Outcome: The result of a trade.

e.g. The quantity or type of resource (items, money, services, etc) a player earns from trading.It is the most noticeable part to players because they trade to gain something they can instantly see.

- Variables: The parameters considered by the simulation to resolve the trade.

e.g. The exchange rate between two resources, the progression level of the player into the story, the reputation level with an NPC, etc…Some of it might be visible to the player, but most of them are part of the mechanic’s black box, behind the scene.

- Context: The meaning of a trade, outside the transaction itself, on a larger scale.

e.g. What this trade means in the player's current strategy, how the state of the world changes what is available or needed, etc…This is the most abstract one for the developers because it is difficult to predict the effects on the player’s decisions.

3. THE 3 SATELLITES’ ACTIVITIES

From the above parameters and my observation of games, I discerned 3 types of recurrent activities around trade:

- Haggling activities serve to improve the outcome (2.) of trade on the player’s side. This covers every situation impacting the price, the cost, or the quantity of resources at stake during a transaction.

- Relationship activities change the level of relationship with an NPC, thus impacting foreground elements, for the player, like new unlocks, stories or quests and background elements like how NPCs behave toward them.

In general, it mostly affects game parts outside of trade like the story tree, but if the reputation or relation is linked to trades, then it will change its variables (2.).

- Economy is the global state and interactions of the game world regarding resources. When we focus on trades, the economy of the world will affect its context (2.) through how things are divided and accessible to the player.

Every game doesn’t use all these activities. It is up to the development team to choose what to include or not in their game.

ADDITIONAL ACTIVITY

As surprising as it might be, I found an additional activity which, at first glance, is completely separated from trades, but its impact was felt a lot during playthroughs. This was:

- Inventory management. The system that bounds the way the player can stock or transport their gears and loots, has nothing to do with trades. However, recently released games have tried to twist the way inventories work and highlighted interesting effects on trade context (2.) and appearance (2.). More details on this later in the paper (8.).

This also opens the possibility to discover that others a priori unrelated activities may have an interesting impact on trade.

4. GAME ACTORS

In terms of in-game integration, these activities are built on top of 3 major actors whose composition impacts the related activity.

- Player: include both the player character (PC) and the player itself. There are 3 main attributes which characterise this actor and define some nuances for trades.

- Statistics & Skills: The PC statistics (e.g. speed, charisma, etc…) and the skills unlocked (e.g. in the case of a skill tree).

- Reputation: Any system that gives a level of reputation attached to the PC toward factions or specific NPCs.

- Actions: The consequences of the player's direct actions in the game.

- NPC (Non-Player Character):

- Behaviour: The bones of the NPC. Composed of a set of rules that command the array of actions available to them in any given situation.

- Personality: The flesh of the NPC. What makes them feel like a living character in the world, such as their likes and dislikes (if any) that will influence their relation toward another character.

- World: is composed of 2 main attributes.

- Simulation: The running simulation of systems in the game world. It covers non-scripted (emergent) interactions that happen based on the set of rules of the simulation.

- Story: Covers the plot and the state of the world based on scripted events, including story branches where the player has an impact since it is pre-made.

In any game, the tweaking of these actors is a way to impact how the game plays, feels and the effects on the game activities.

Now is a good time to take a look back at Figure I and make a good understanding of the relations mentioned above between the transaction mechanics (1.), the 4 parameters (2.), the satellite activities (3.) and the 3 actors (4.); before going into the details of the mechanics present in the activities around trade.

5. THE MECHANICS OF HAGGLING.

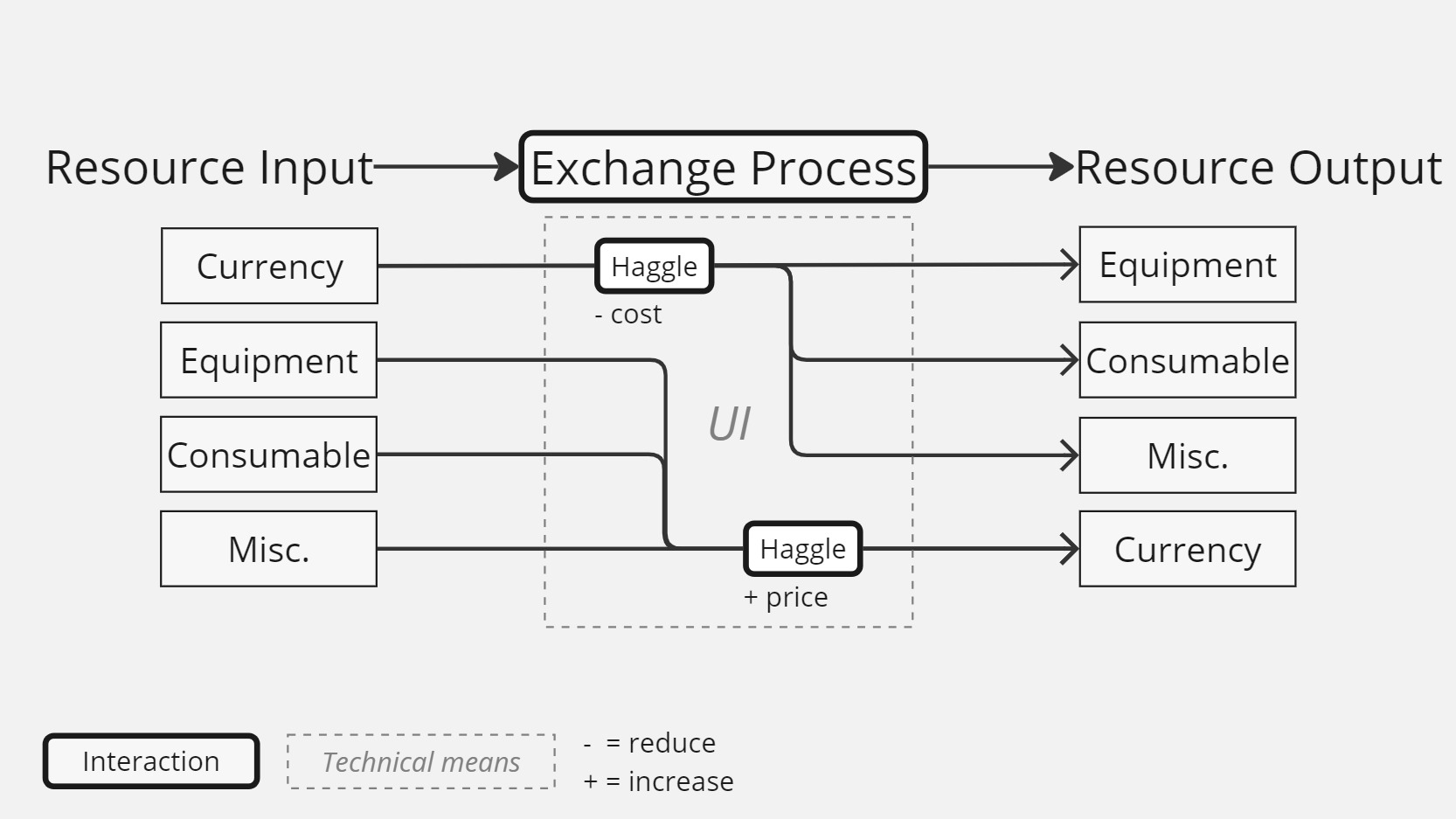

A haggle is a negotiation around a set of goods between the seller and customer to change the outcome (2.) of a trade. In real life, it needs to satisfy both sides to be considered successful, but in video games when the player interacts with an NPC, it is mainly a means to maximise the output for them in negotiable transactions. It mostly works as depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The impact of Haggling during a transaction

During my analysis of games, I found that most used haggling mechanics can be assembled under 4 types.

PLAYER’S STATISTICS & SKILLS

In most role-playing games, a player’s haggling or negotiation skills and some statistics (like charisma) will have a passive effect on prices, either reducing costs and/or increasing selling prices based on a percentage. This use can be considered abstract haggling because it applies passively to the shops and doesn’t add any new elements to the game.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Divinity: Original Sin 2 ”(2017) in shops, “Octopath Traveler II”(2023) in shops, “The Elder Scroll V: Skyrim”(2011) in shops.

TUG-OF-WAR

Illustration: Tug-of-war between two opponents

Tug-of-war consists of pulling a slider between two extremes to get the best outcome, to the detriment of the opponent. Various factors from the player and the NPC will influence the “strength” at which the player can pull the slider to their advantage.

The slider can be visible like in “Kingdom: Come Deliverance”(2018), with hard limits the player can not exceed and a visual representation, or invisible like in “Star Fox Adventures”(2002) where the merchant asks the player to guess in the right price bracket to buy an item.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Receattear: An Item Shop Tale”(2007)” choosing the selling price of items, “The Elder Scroll IV: Oblivion”(2006) haggling in shops, “The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt”(2015) haggling over contracts.

DIALOGUE THRESHOLD

In some games, it is possible to engage in a dialogue with a trade NPC to haggle with them. The condition for this type of choice to be available is generally to reach a threshold in a specific player’s statistic (like charisma or negotiation). In some cases, the choice is already available but triggers a die roll that defines if the player's action is successful or not.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Disco Elysium”(2019) during arguments with NPCs, “Vampire: The Masquerade – Swansong”(2022) in confrontations.

However, I have seen no game choosing to treat haggling with dialogue tree choices. I believe it can, and probably exist, but I did not found one.

MINI-GAME

Mini-games are autonomous small portions of gameplay that can be played on their own, aside from the main gameplay, or be integrated inside a side-activity. They can take many forms and usually test a single player skill [4] at a time to stay low in scope. The performance of the player during these mini-games will influence the rewards they get from the activity.

They are used to insert a side gameplay into a side activity, encouraging the player to engage with it for marginal profit. Haggling mini-games generally challenge action skills [4] to emphasise the argument with an opponent.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Great Houses of Calderia”(2024) to resolve trades’ negotiation, “Potion Craft: Alchemist Simulator”(2021) when selling a potion.

6. THE MECHANICS OF RELATIONSHIP

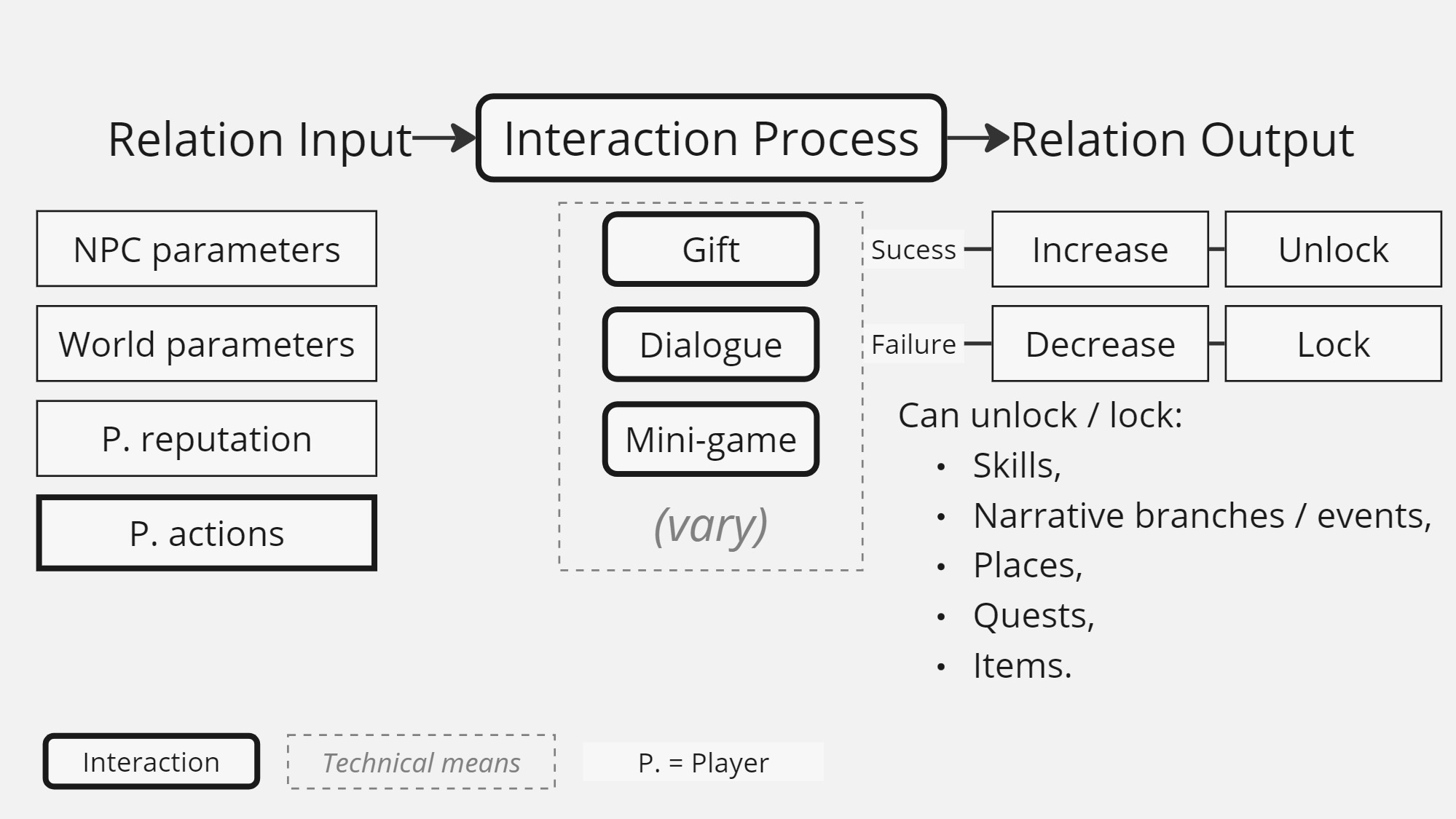

Relationships between characters are used for both narrative and/or gameplay purposes. They can symbolise conflicts between characters or reflect the player’s actions. Figure 6.a represents the model for such an element.

Figure 6.a: Model of Relationship System

In the context of trade, the relationship between the customer and the vendor has a passive effect on the transaction or haggling by tweaking the variables (2.). Relationship is something that the player is most likely to influence from outside trade activity.

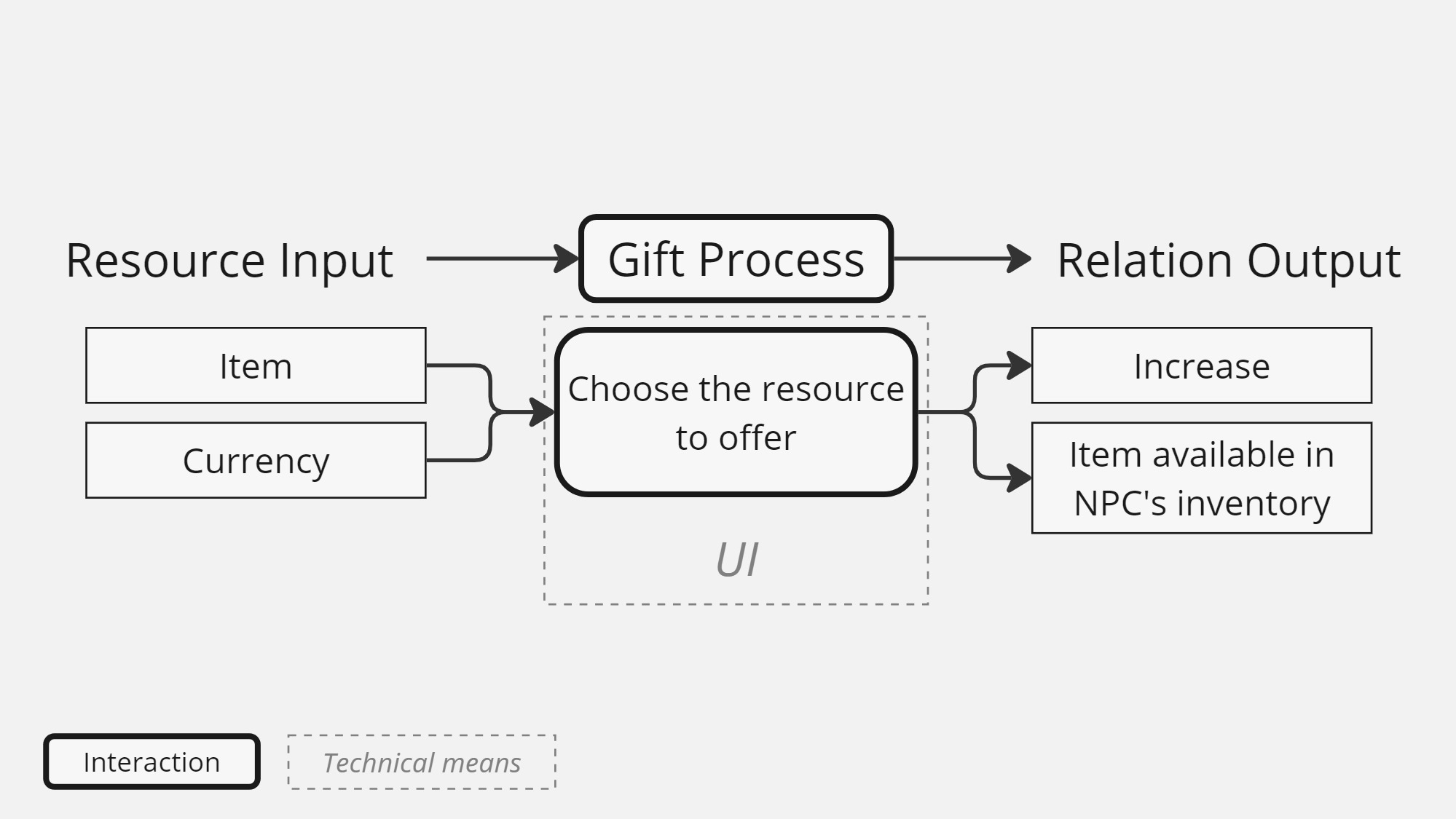

GIFT

When there is a gifting mechanic in a game, it is the easiest way to increase your relationship with an NPC. A gift consists of offering a free resource to an NPC, sometimes based on their preference. If they like it, the player relation with this NPC will increase. Illustrated by the Figure 6.b.

Figure 6.b: The Gift mechanic

Depending on the game, the gift might be available to any non-enemy NPC no matter their roles or restricted to vendors, non-vendors or/and romantic interest NPCs.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Animal Crossing: New Horizons”(2020), “Persona 5”(2016), “Stardew Valley”(2016).

DIALOGUE CHOICE

When engaging in dialogue with an NPC, if the game allows the player to choose how to answer, it might also change the relationship with this NPC. This is present in visual novel games where dialogue is the centre of the gameplay; many role-playing games also use this system.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Baldur’s Gate 3”(2023) dialogue-tree, “Detroit: Become Human”(2018) dialogue-tree, “Jack Jeanne”(2021) dialogue-tree.

However, for the dialogue to impact the trade, the relationship must connect to it in some way.

MINI-GAME

Mini-games are autonomous small portions of gameplay that can be played on their own, aside from the main gameplay, or be integrated inside a side-activity. They can take many forms and usually test a single player skill [4] at a time to stay low in scope. The performance of the player during these mini-games will influence the rewards they get from the activity.

Mini-games are used in some games to increase the relationship with an NPC by winning at a mini-game. They generally challenge more mental skills [4] to represent the pace of a discussion.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Ace Attorney Investigations 2: Prosecutor's Gambit”(2011) quick time dialogue-tree during “Mind Chess” battles, “Divinity: Original Sin”(2014) rock-paper-scissors to persuade an NPC, “The Elder Scroll IV: Oblivion”(2006) flattery wheel to bribe people.

7. THE MECHANICS OF ECONOMY

The economy in a game world has 2 sides. In one case, the player can not interact with it, the economy is set in stone by the developers from the start to the end of the experience. This can be found in games with linearity in their levels, narrative, or gameplay; as well as some exploration or adventure games.

In the second case, the player can influence it through gameplay, or narrative choices. This is more common in management, role-playing, or sandbox games. Some of these games generally try to simulate a real-world-ish economic system.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Resources that are available in shops are generally things like items, consumables, and craft materials. Their availability will determine how they are accessible in the world, leading to the behaviour of the player and NPCs alike. There are a few questions to answer when looking at a resource:

Is the resource available:

- In every shop.

- Only in specialised shops.

Is the price for this resource:

- Identical game-wide.

- Changing locally based on the shop’s parameters.

- Evolving along the game’s progression, narrative.

SUPPLY & DEMAND

Supplies & demands are found in every game trying to simulate an economic system. It can be ultra-simplified or trying to model the real-world economy as closely as possible, in service of the game experience. A supply & demand system will look like Figure 7.

Figure 7: Supply & demand mechanic

The variations will impact the world’s simulation (4.) thus changing the context (2.) of future trades.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Anno 1800”(2019), “Mount & Blade II: Bannerlord”(2020), “Read Dead Redemption 2”(2018).

RANDOM EVENT

Random events are a great way to change the state of the game world during a playthrough. They are pulled from a pool of possibilities and impact the player’s journey.

In the context of trade, random events can impact the supply & demand chain (7.) or the availability of resources (7.) and also relationships (6.).

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Battle Brothers”(2017) with village raids, “Griftlands”(2019) with random encounters, “Victoria 3”(2022) events.

PASSIVE INCOME

Incomes from a virtual plots of lands or buildings or services, generally owned by an NPC, which can be bought by the player to give them a passive income they can collect at specific places. The income stock will take some time to renew itself, either in-game or play time. In some games, buying a real estate also unlocks crafting stations, special gears and shops, or a customisable place to decorate.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: ”Assassin's Creed Unity”(2014), “Fable III”(2010) when buying propriety, ”Final Profit: A Shop RPG”(2023).

8. THE MECHANICS OF INVENTORY MANAGEMENT

The player inventory is the place for the player to stock resources they can use later during the game. At first glance, it only impacts the player, but the rules and limits placed on the inventory system impact the context (4.) of trade. Some games have found ways to create challenges in managing the inventory, this challenge also impacts trade.

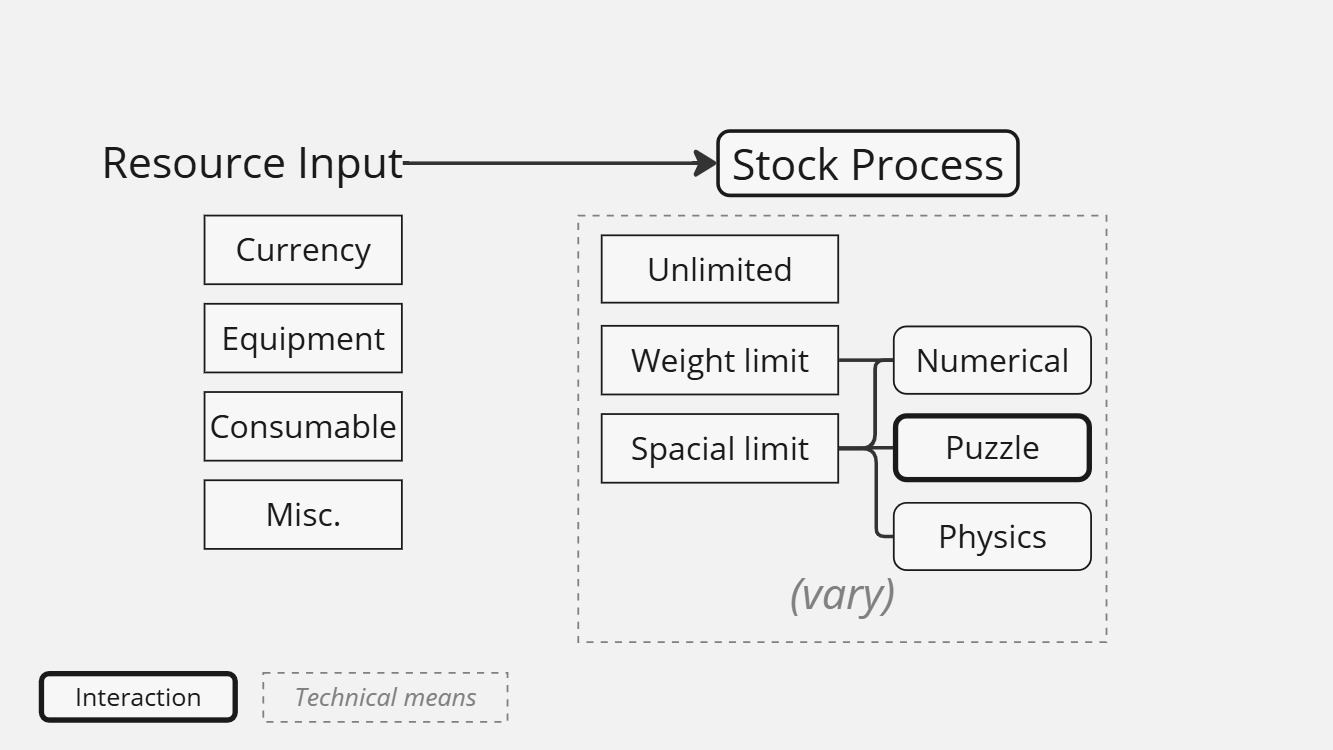

I use these rules and limits to categorise the types of inventories. Figure 8 illustrates this.

Figure 8: Different mechanics of inventory management

Games can use different types of inventories based on their need for the player experience.

UNLIMITED

These are inventories that don’t place any limit on the resources they can stock (outside hardware capabilities concerns).

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Chained Echoes”(2022), “Kingdom: Come Deliverance”(2018), “Like A Dragon 7”(2020).

WEIGHT LIMIT

The available stock is limited by the total weight of the stocked resources. Weight is a numerical value put on any resource that can be stocked.

This system serves to limit the player's ability to carry an excess of resources, while still allowing them to choose what they care more about to transport.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Baldur’s Gate 3’’(2023), “The Elder Scroll V: Skyrim”(2011), “The Long Dark”(2017).

SPACIAL LIMIT

The available stock is limited by the number of slots. And every resource requires a certain number of slots.

I found 3 types of interaction used in games:

- Numerical interaction: Each resource takes a slot (no matter its type) and there is a limited amount of them in total.

- Puzzle interaction: Generally it uses a grid to represent the inventory space, each item has a shape and must fit into available space on the grid to be stocked.

- Physic interaction: The inventory and resources are physically simulated by the game and will bounce out of the inventory if they don’t fit.

This system allows for more nuanced control of the inventory and has been used to create new interactions about inventory management in games.

A few examples of games using this type of mechanic are: “Dredge”(2023) has a puzzle boat inventory, “Kingdom: Classic”(2015) has a physical inventory for coins, “Minecraft”(2009) has a numerical inventory.

II. ASSESSMENT OF TRADE MECHANICS

Now that we have an overview of the mechanics used with trade, we can wonder if these mechanics are really effective in delivering a gameplay experience to the player in comparison to the traditional use of the shop interface. How far the existing games have pushed these mechanics? What are the flaws or difficulties bound with them?

First, I will explain the method I used to evaluate a game mechanic, and then I will show a few case studies from mechanics present in the previous chapter.

1. LENSES FOR GAME MECHANICS

To conduct an in-depth analysis of the trade mechanics, I am using a series of lenses under which I examine each mechanic. These lenses were formed based on my readings regarding game mechanics.

A game mechanic is fun when the player is led to solve the black box of a mechanic through the process of discovery, exploration, and mastery [1]. And use this knowledge of the mechanic as a tool to overcome obstacles [3].

From this statement, I established 4 lenses: the form, the substance, the learning curve and the variety. Now I will enter in details about each one of them.

FORM

First, about the form of a game mechanic, since it is the point at which the developers have less and less impact further in the production.

The form is the given context, appearance, and presentation of a mechanic through the game. It delivers through the visuals, universe, effects, sounds, and gameplay. The form will inevitably have a first impact on the player’s likes or dislikes of a game or mechanic.

e.g. In “Dooms Eternal”(2020), if a player is disgusted by the gore aspect of an enemy execution, a mechanic which serves to regain HP and ammunition, they might tend to dislike the game or the way the mechanic is represented regardless of its usefulness in the game.

The form’s appealing to the target audience is essential to make a good first impression and encourage the player to play the game [3].

SUBSTANCE

The substance is the uses the player will have for this mechanic in resolving the challenges. The actions that can be performed by the mechanic are part of the black box when starting the game [1]. Mechanics are like tools the player can choose when thinking how to approach a situation.

Knowing the substance of a mechanic enables one to understand its gameplay possibilities and put it into the context of the whole game.

LEARNING CURVE

To exploit the substance of a mechanic, the game needs to teach its different uses gradually through the learning curve, while also maintaining the motivation to play the game and use the mechanic.

The learning curve can be broken down into 3 distinct phases: discovery, exploration and mastery. Each one with a different goal, challenge, and depth [1].

- Discovery is the intrinsic challenge of the player experimenting with the mechanic for the first time, trying to understand its basic workings.

In the end, the player is toying with the mechanic and does not use it actively yet.

- Exploration is the extrinsic challenge of the player learning how to use the mechanic in the environment to achieve a goal.

This exploration is built by putting the player against gradually harder obstacles to overcome. In the end, the player has learned the mechanic and can use it actively in ordinary situations.

- Mastery presents more complex extrinsic challenges where external factors modify how the mechanic behaves. Either in its execution or the actions resulting from it. This requires new learning from the player to use it in extra-ordinary situations.

Challenging the mastery of the mechanic through the game keeps it engaging and prevents it from becoming too predictable. In the end, the player feels they have mastered all the possibilities given by the mechanic [3].

The motivation is maintained by avoiding frustration or burnout by following some guidelines [3]:

Balancing:

- The effort and time required to learn how a mechanic works,

- The effort and time spent on using what has been learned (on various challenges),

- And the payoffs of the usage of the mechanic (in both actions capabilities and rewards).

In summary, well-made tutorials and pacing will increase the quality of a mechanic by allowing the player to exploit its full potential.

VARIETY

Bringing variety into game challenges is a necessity to create relevant obstacles alongside the mastery of the player, but we rarely think about what creates variety inside a mechanic itself.

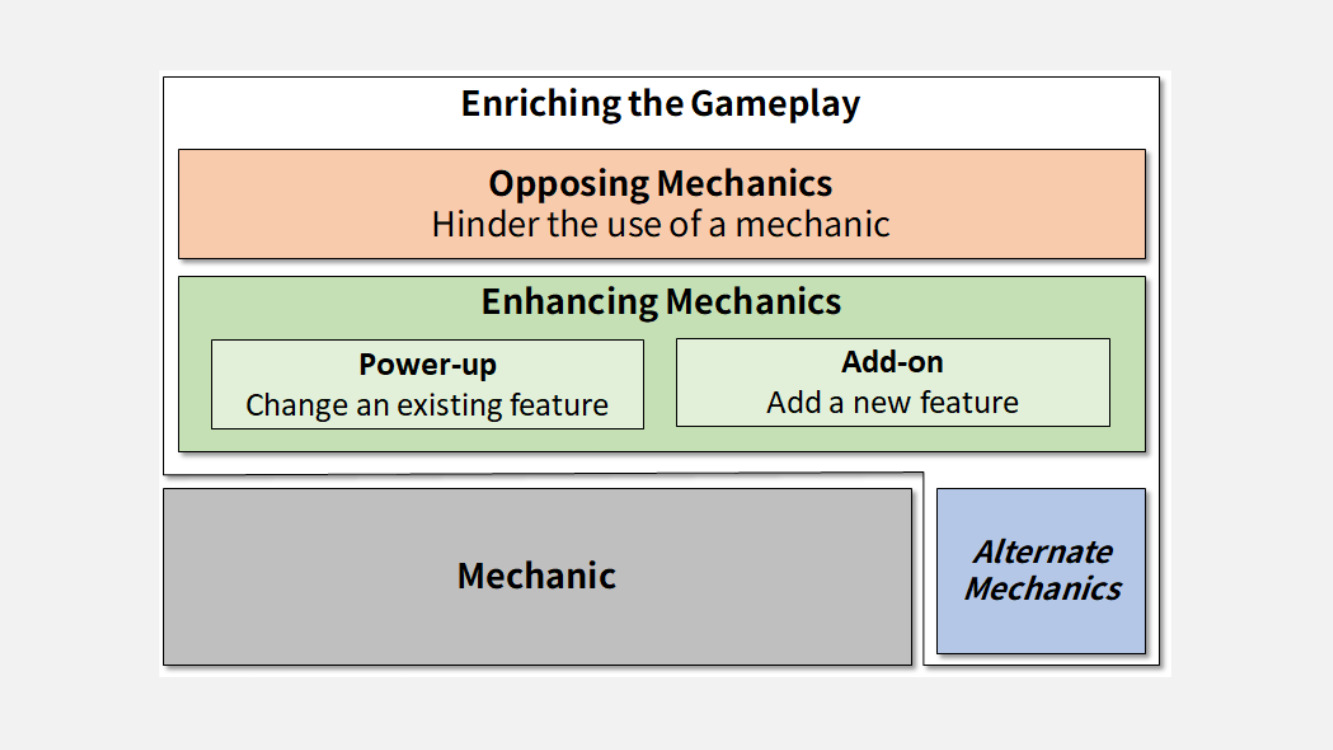

A great way to create variety is to create interconnected mechanics on top of foundations. Figure 1 is a model that highlights the role of interconnected mechanics. It can be used to discover new angles to expand an existing mechanic to enrich the gameplay without increasing its complexity.

Figure 1: An architectural model for game mechanics [3]

- Mechanic: The foundation of the ensemble. A mechanic used to accomplish a player activity. Generally, one of the core mechanics.

- On top of that are build sets of mechanics that answer different roles to enrich the gameplay.

- Enhancing mechanics: Reinforce the mechanic in two ways:

- Power-up: Modify an existing feature from the mechanic to empower it.

- Add-on: Add a new feature to the mechanic and change the way it plays as well as its outcomes.

- Opposing mechanics: Hinder the mechanic by troubling their utilisation or result.

- Alternate mechanics: Offers alternatives to carry the same result as the mechanic, but through a different one.

- Enhancing mechanics: Reinforce the mechanic in two ways:

Bringing variety into a mechanic allows it to develop its potential for mastery. Then it can be used in the learning curve (1.) process.

When analysing an existing mechanic, it is relevant to know what role they fulfil to adjust expectations and focus the work toward their role. A production cannot afford to enrich every present mechanic, they generally focus on a few core-mechanics of the game and expand around it.

2. CASE STUDIES

With the case studies, I show examples of some analysis I made with the lenses. Each case ends with my personal judgement on the mechanic analysed, and more specifically the one from the game it was taken from.

The lenses’ analysis is not here to give a final judgement on a mechanic in a game, since its integration and other mechanics available will also influence how it is perceived by the player. However, it can pinpoint various flaws and strengths that we can choose (or not) to work on as developers.

TRADE CASE STUDY

The mechanic from Figure I in chapter I. represents the most basic use of a shop to trade with an NPC. Therefore, it is interesting to analyse with the above lenses.

Form: Generally it uses user interface panels.

Substance: Trade serves to transform an excess of unwanted resources into new resources the player needs.

Discovery: Tutorials are not needed since the mechanic is omnipresent in most games that its uses are already well known.

Exploration: The mechanic doesn’t challenge the player on anything. They will mostly navigate the user interface to find what they want to trade.

Mastery: Thus there is no mastery challenge either.

Variety: The only variety I observed is in the alternate mechanic of looting. Loots have the same result as trade by providing resources; however, those are random in type and quantity and cannot be chosen by the player (except when a specific area or target provides a designated type/amount of resource).

Traditional trade in games is not interesting from a gameplay perspective because it doesn’t propose any gameplay challenge to solve. The black box is also expounded from the start because players already know the ins and outs of this mechanic.

The closest challenge I found is the choice the player makes for what resource to sell and buy, this generally depends on the context of the game and the current player's situation when doing the trade.

MINI-GAMES: A HAGGLING CASE STUDY

Mini-games are used in numerous games because it is a reliable side-activity which is well accepted by players, easy to scope and teach.

They are used in relationship and haggling activities. For the latter, the player is generally the shopkeeper and not the client. This in itself is an opportunity for some development.

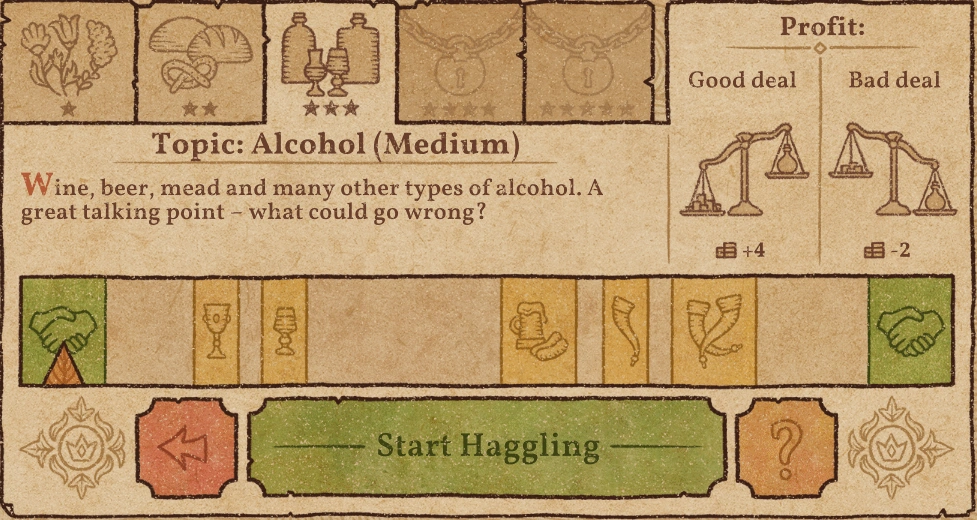

However, most mini-games suffer the same flaws we will observe with the analysis of the timing mini-game from “Potion Craft: Alchemist Simulator”(2022).

Screenshot: timing mini-game from “Potion Craft: Alchemist Simulator”(2022)

In this mini-game, the arrow will start moving back and forth between the 2 handshake zones at both extremities. To succeed in striking a good deal, the player needs to click when the arrow hovers over one of the centred drinking glass icons to gain more money from the transaction before concluding the deal. Missing them will decrease the value of the transaction for the player.

Form: The interface matches the art direction of the game. Medieval-ish inspired icons with parchment texture.

Substance: The mechanic allows to gain/lose more money from a transaction, based on the player's performance.

Discovery: Tutorial panels explain the rules of the mini-game.

Exploration: Haggling can be used on every single client or merchant the player meets. Later on, they can change the difficulty of the mini-game, which will increase the speed of the arrow and tighten the centred icons size.

Mastery: In the long run, there is no extra-ordinary situation or change made to the mini-game. When the player learnt to use it during the exploration phase, they already mastered it.

Variety: There are no mechanics enriching the gameplay of the mini-game. The alternate mechanic would be to skip the mini-game to get an average amount of money without engaging with its gameplay.

The consequence of lacking a mastery phase is that the mechanic doesn’t renew over time and becomes repetitive at some point. Some mini-games closer to puzzles can mitigate the lack of difficulty by proposing more challenging puzzles overtime, but they still rarely add extra-ordinary situations for the player to face.

Most mini-games are not suited to being played for a long period. Swapping between different mini-games or developing their mastery phase are ways to counter this burnout.

TUG-OF-WAR: A HAGGLING CASE STUDY

Tug-of-war is a push and shove activity where victory is to the direct detriment of the opponent. It is a binary option that is most present in games though an abstract form like territory capture, or score. When there is a unique reward that cannot be shared or possessed by multiple actors, then it mostly takes from tug-of-war. It is the most straightforward form of conflict.

It is used in haggling activities to embody the conflict during negotiation between the player and the NPC, over the price of an item.

Screenshot: Tug-of-war haggling in “Kingdom: Come Deliverance”(2018)

In this context, the base price of the item is 115 and the player will make an offer to buy it for 105 coins value. When the player makes their offer, the NPC can either accept it, or refuse it: lose 1 patience and propose another price between the initial cost (115) and the player’s offer (105). The player can then make another offer, higher, or lower, until the deal is accepted, or the patience runs out. If the patience of the NPC reaches 0, the deal is cancelled and the reputation with this NPC is damaged.

Form: The tug-of-war interface appears on the side of the screen to keep the focus on the characters haggling. Camera shots and reverse shots will trigger with the dialogues between the player character and merchant, making offers and counteroffers, in order to keep the role-playing aspect and go beyond the use of an interface to chose the prices.

Substance: The mechanic serves either to make saving when buying some items or, if the player pays the merchant more than what they asked, to gain reputation towards them.

Discovery: Tutorial panels explain the interface of the tug-of-war.

Exploration: Haggling can be used with any merchant, and the player will always initiate the haggling by themselves.

Mastery: In the long run, there is no extra-ordinary situation or change made to the tug-of-war. When the player learnt to use it during the exploration phase, they already mastered it.

Variety: There are no mechanics enriching the gameplay of the tug-of-war. The alternate mechanic would be to skip the haggling and pay the full price of the items.

Like for mini-games (2.), the consequence of lacking a mastery phase is that the mechanic doesn’t renew over time and becomes repetitive. It can be more serious for tug-of-war because they can be abused more easily due to the ‘one-way to win’ of the mechanic.

However, in “Kingdom: Come Deliverance”(2018) there is a lot of others gameplay to engage within this medieval open-world RPG and enough time may stand between haggling phases, to renew the player interest. Moreover, the option to tip a merchant to gain more reputation adds a soft bargaining [5] option and leans to play on the player’s empathy toward merchants they learnt to know.

SPATIAL LIMIT — PHYSIC: AN INVENTORY MANAGEMENT CASE STUDY

Inventory management is present in any game that lets the player store more than a handful of items. It forces the player to choose what they want to keep and discard from their inventory. It can serve the fantasy, the role-play of the game or, be a real challenge and add tension due to the limit for the inventory like in survival games.

Like we discussed earlier, most games will use trade to complement the limit of the inventory by allowing to exchange items for currency or needed items. And the limits of the inventory have a great impact on the context of trade because the player needs to consider how their new purchase will fit in the limits of the inventory.

In this case study, I intend to examine the least utilised type of limitation I have seen for inventories. An inventory with physics simulation.

Screenshots: Money purse in “Kingdom: Classic”(2015)

In this game, the player will move to the left and right of their land to build fortifications and defend their kingdom against night monsters. To achieve that, they need to hire peasants to work the land, buy weapons to hire soldiers and hire builders for the fortifications. They earn money by finding treasures in the wild land or collecting taxes from the peasants. The coins they collect will drop into the money purse on the top-left of the screen and fill it until it is full. When full, collecting more coins will make it overflow and the player may lose the falling coins in the river. Additionally, the health points of the player and the NPCs are equal to the number of coins they carry.

Form: The coin purse is a diegetic interface that fits the medieval-fantasy theme. It visually moves a lot with the increase and decrease in coins and creates satisfaction when it is full.

Substance: The mechanic stocks coins by piling them up and makes them available to use for the player.

Discovery: A tutorial gameplay sequence will teach the player by making them collect their first coins. The physic simulation also makes the mechanic easily understandable at first glance.

Exploration: Collecting coins is one of the core activities of the game, but the player can not influence the falling of the coins.

Mastery: When the purse is full, the player needs to learn to avoid collecting more coins to not waste some when it overflows the purse.

Variety: There are no enhancing mechanics for the coin purse, since it has no upgrades or special status. The opposing mechanic is the overflow status by itself, since it leads to a change of strategy to not waste coins. An alternate mechanic to store coins would be the soldiers of the kingdom, which can store a few coins on themselves if given, which strengthen their health point by the same occasion.

This way of handling inventory seems well-balanced for small-scale experiences. It has something to offer for each of the lenses but stays condensed and straight to its point. This is not a surprise when considering the scope of “Kingdom: Classic”(2015) which is a 5~10-ish hours game.

However, I think the appeal of the mechanic reaches a higher level for a simple reason. This mechanic is a good toy [4][5][6], even without the intricacies of the gameplay, there is something hypnotising to watching the coins filling the purse.

The mechanic is pretty unique and makes me wonder if it could be used in other games with trade activities.

ABOUT TRADE AS THE CORE-GAMEPLAY

Lastly, I would like to address a few words to games that chose to make the player managing a shop, sedentary or moving from places to places, the core fantasy of their experience. Even if they were not the primary focus for this analysis, it is obvious that these are the spearhead in using mechanics to improve trade because their core-gameplay is focused around this experience. They generally make one of the satellites’ activities their core-gameplay, either in mechanics or in theme only. A few examples of games with trade as the core-gameplay are: “Potionomics”(2022) a deck-builder focused on relationship, ”Final Profit: A Shop RPG”(2023) an incremental RPG focused on shop management and story and ”Merchant of the Skies”(2020) a travelling merchant fantasy focused on the economy of the game’s world.

The goals, tasks, and victory conditions for the player are related to these activities instead of what we generally find in games. Hence, why it is not a particularly good example to follow when trade is only a side activity of your game. However, inspiration and innovation might come from these games and lead to adaptation in other experiences.

REFERENCES

[1] Daniel Cook (2006), What are game mechanics? - lostgarden.com

[2] Cambridge Dictionary, Meaning of trade in English - dictionary.cambridge.org

[3] Carlo Fabricatore (2007), Gameplay and game mechanics design: a key to quality in videogames - researchgate.net

[4] Jesse Schell (2007, 2014, 2019), The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses

[5] Nicolae Berbece (2022), The Most Underrated Mechanic In Games - Mental Checkpoint YT

[6] Keerthik Omanakuttan (2014), Toys To Games: A Game Design and Analysis Framework - medium.com

Extra Credits (2022), Shopping in Games is Garbage but it doesn't have to be! - Extra Credits YT

Daniel Cook (2007), The Chemistry of Game Design - lostgarden.com

Raph Koster (2004, 2013), Theory of Fun for Game Design

Dan & Mike at Design Doc (2024), What Makes A Great In-Game Shop? - Design Doc YT

TRADEMARKS

Every game referenced or shown is a registered trademark of their respective owners.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am extremely grateful to my supervisor and the Tokyo University of Technology for allowing me to work in their facilities, as well as my Japanese teacher who helped me with all the paperwork regarding moving to Japan. Many thanks to the defence committees and close cohort members for their regular feedback and support. I would also like to acknowledge my family for their moral support and outsider’s perspective on my work. Lastly, I want to mention the staff at ISART Digital Paris for their help in sending the topic proposal to the university.

.jpg)